The Secret Police

When Margarita asked Woland to be returned with the master to the basement in the lane off the Arbat, the master said: «Ah, don't listen to the poor woman, Messire! Someone else has long been living in the basement, and generally it never happens that anything goes back to what it used to be». But Woland said: «That's true. But we shall try». And he called out: «Azazello!» At once there dropped from the ceiling on to the floor a bewildered and nearly delirious citizen in nothing but his underwear, though with a suitcase in his hand for some reason and wearing a cap. With the suitcase and the cap, Bulgakov referred to the fact that under the Stalin terror many soviet citizens had always a suitcase ready with the most necessary things, just in case of an unexpected visit from the secret police at night.

OGPU/GUGB and NKVD

In the time that Bulgakov wrote The Master and Margarita, the secret police was called the Объединённое государственное политическое управление (ОГПУ) [Obedinyonnoe gosudarstvennoe politicheskoe upravlenie] (OGPU) or Joint State Political Directorate until July, 1934. Then it got renamed into Главное управление государственной безопасности (ГУГБ) [Glavnoe upravlenie gosudarstvennoy bezopasnosti] (GUGP) or Main Directorate for State Security.

The OGPU/GUGP was one of the most important and influential sections of the Народный комиссариат внутренних дел (НКВД) [Narodny komissariat vnutrennikh del] (NKVD) or People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs.

The importance of the GUGB in the NKVD is clearly shown by the fact that it was headed directly by the People's Commissar himself. As a matter of fact, in popular speech the secret police was often called NKVD instead of OGPU/GUGB.

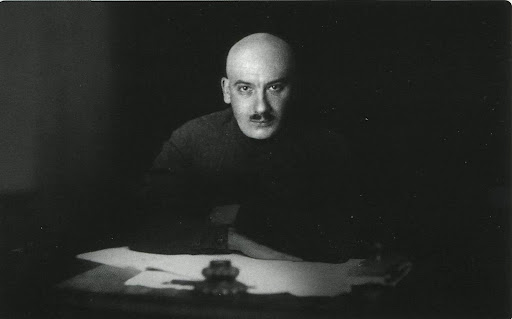

The early predecessor of the OGPU/GUGB was the Cheka, created in 1947 and headed by the infamous Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky (1877-1926). Its full name sounds rather hilarious: Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия по борьбе с контрреволюцией и саботажем [Vserossyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissia po borbye s kontrevolyutsney i sabotazhem] or All-Russian extraordinary commission for combating counterrevolution and sabotage. The Cheka worked under direct supervision of the Sovnarkom. Later the organisation was renamed GPU (1922), OGPU (1923) and GUGB (1934), and moved to the NKVD. In 1953, the organisation was reformed to the Комитет Государственной Безопасности (КГБ) [Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti] (KGB) or Comittee for State Security.

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky

The OGPU/GUGB had three successive leaders and they all would become notorious: Henrikh Grigorevich Yagoda (1891-1934) - who would get a role in The Master and Margarita - Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov (1895-1940) and Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria (1899-1953). Not one of them died from a natural cause. The first two were liquidated by Stalin, the third survived him for some months, but he was arrested shortly after Stalin’s death by Nikita Sergeevich Krushchov (1894-1971) and executed.

Henrikh Grigorevich Yagoda

The NKVD was responsible for a state terror carried on against dissident writers, jewish intelligentsia, scientists and dissenters like catholic and orthodox priests. No effort was avoided to make the lives of non-communists a misery, to pursue them, to kill them or to burst into their houses for «investigating subversive activities». Dissidents refusing to conform to the communist ideology, could be placed under restraint in a psychiatric hospital. All who had appearances against, could be confronted with the service.

The Особое Совещание [Osoboe Soveshchanie] or Special Council of the NKVD was created by decree of July 10, 1934 - it was the same decree by which the NVKD itself was created. This Special Council was authorized to impose «administrative sanctions», without intervention of a court. It could be banishment, labour camp for a maximum of 5 years, or deportation out of the USSR. As from 1936, the Special Council could decide to 25 years of labour camp or even death penalty.

The labour camps were managed by another special department of the NKVD, the Главное Управление Исправительно-Трудовых Лагерей и колоний [Glavnoe Upravlenie Ispravitelno-Trudovikh Lagerey i kolony] or Main Directorat for Corrective Labour Camps and Colonies, which was created in 1929 and also well known in the west under its abbreviation ГУЛАГ or Gulag.

NKVD-agents were not only executers. Often, they were victims of the repression themselves. Most members of the NKVD-staff in the thirties were arrested and executed.

NKVD-troika's

Troika's (threesomes) were commissions of three people often employed in the organisation of the society by the bolsheviks. It was recognized that three persons is the minimal number required for collegiate decisions: this is a minimal number for which voting, a necessary instrument of democratic decisions, was reasonably possible, and they were used on many levels and in many area's. There were operational troika's (оперативная тройка), juridical troika's (судебная тройка), exceptional troika's (чрезвычайная тройка) and special troika's (специальная тройка).

A NKVD-troika (НКВД тройка) was threesome used as an additional instrument of extrajudicial punishment. It was introduced to supplement the legal system with a means for quick punishment of «anti-Soviet elements». The chairman of a NVDK-troika was, in general, the chief of the corresponding territorial subdivision of the NKVD. The second member usually was the prosecutor of the republic, krai or oblast in question, and the third person was usually the Communist Party secretary of the corresponding regional level. The decisions of the troika were passed to the corresponding operational group that had to execute the punishment. Time and place of the executions had to be kept secret.

Order # 00447

On July 30, 1937 the Order # 00447 of the NKVD was issued. It was about «the repression of former kulaks, criminals, and other anti-Soviet elements». By this order, NKVD-troika's were created at the level of republics, krais and oblasts. Investigation was to be performed by operational groups, «in a fast and simplified way», and the results were to be reported to troikas for trials.

According to the instructions, «kulaks, criminals and other anti-Soviet elements» had to be divided into two categories. The first category was to be shot, the second to be deported to the labour camps. Each category had defined quota by region. For Belarus, for instance, the quotum was estimated at 2.000 people in the first category and 10.000 in the second. Which made a total of 12.000 anti-Soviet elements. The quota were estimates and, as a principle, could not be exceeded without the personal approval of Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov (1895-1940), nicknamed the dwarf, who was the chief of the NKVD from 1936 to 1938, during the most deadly period of Stalin's Great Purge. But it was not hard to get such approval. One and a half month after the announcement of the Order, some 101.000 arrests were made, and 14.000 convictions were pronounced. The norm for evidences was quite low: a tip from an anonimous informant could be sufficient for an arrest, like experienced Nikanor Ivanovich Bosoy in The Master and Margarita, shortly after a telephone call of Woland's «interpreter» Koroviev. According to the NKVD Order # 00486, the family of the suspects, including the children, was automatically suspected as well.

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov

In 1938 the NKVD troika's which were created by Order # 00447, were abolished again.

The NKVD and the Soviet economy

The widespread system of working in the Gulags contributed considerably to the Soviet economy and the development of remote regions. The first laws related to the labour camps mentioned the explicit objectives to colonize, for instance, Siberia. Mining industry and the construction of roads, railways, canals, barrages and factories in the labour camps featured largely in the plan economy and the NKVD had its own production objectives.

A special aspect of the realisations of the NKVD was the role played by the service in the advancement of sciences and the development of weapon systems. Many researchers and engineers who were arrested and convicted for political crimes were put in a privileged prison, a шарашка [sharashka]. Etymologically, the word sharashka comes from the Russian slang expression шарашкина контора [sharashkina kontora] or office of thieves. A sharashka was much more comfortable than a camp of the Gulag. The scientists were obliged to further develop their specialties and some belonged to the world top in their area. One of them was, for instance, Sergei Pavlovich Korolyev (1907-1966), the chief designer of the Soviet space programme and of the first manned spacecraft in 1961, another one was Andrei Nikolayevich Tupolev (1988-1972), the famous airplane designer.

After World War II, the NKVD coordinated the work to be done jn the nuclear arms race, under the direction of general Pavel Anatolevich Sudoplatov (1907-1996). The scientists in this programme were no prisoners, but their work was coordinated by the NKVD because it was closely connected to intelligence, so confidentiality was an important issue. And confidentiality, yes, that was the NKVD's specialty.