The Russian Bards

Singer-songwriters

The movement of the singer-songwriters or the Russian bards in the Soviet Union is based on the tradition of the авторские песни [avtorskiye pesni] or author songs, which originated in the late nineteenth century. The authors of these songs, for which the music was subordinate to the lyrics, performed their own work, often accompanying themselves on a Russian guitar which, unlike most other guitars, had seven strings.

The songs of the bards had no commercial intentions. They didn't need so much to be sold, they needed to be sung. Therefore, and also because of the quirky lyrics that often were a thorn in the side of the Soviet regime, the songs of the bards in the Soviet period were rarely recorded and distributed by the State company Melodiya. Usually they were, with their simple melodies and only accompanied by an acoustic guitar, picked up by amateurs who passed them again to other amateurs, or they were distributed through the magnitizdat. In this way, the songs of bards known as Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava (1924-1997), the poet of the Arbat, and Vladimir Semyonovich Vysotsky (1938-1980) got known across the Sovet Union and beyond.

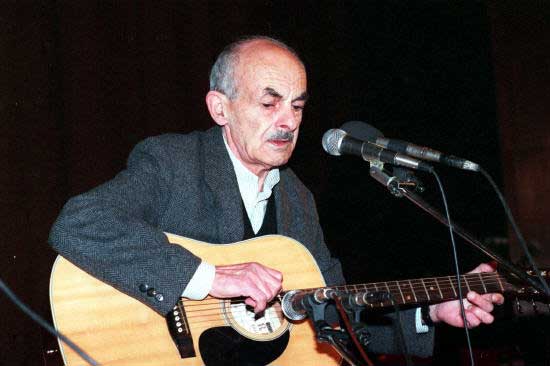

Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava

Here you can listen to the song Черный кот [Chorny kot] or The Black Cat by Bulat Okudzhava, the bard of the Arbat.

Vysotsky was immensely popular. As an actor, he was accepted by the Soviet authorities, but not as a singer or a poet. About his songs, he said himself: «They were impressions in verse and encased in a rhythmic pattern. I grabbed my guitar, began strumming a bit and then there was something like a song. Actually, it were not songs. As I see it, it were more like poems that you should carry with instrumental accompaniment. In short, rhythmic poetry.»

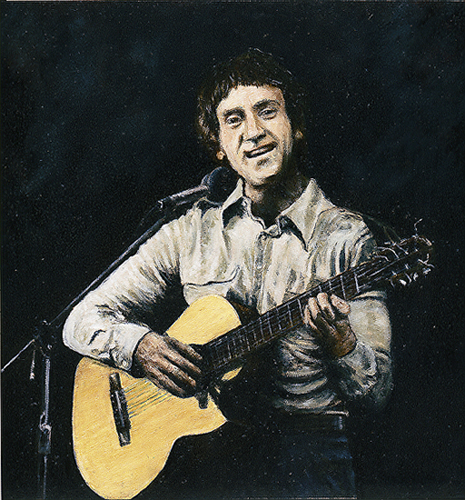

Vladimir Semyonovich Vysotsky

Here you can listen to the song Баллада о люби [Ballada o lyubi] or Ballad about Love by Vladimir Vysotsky.

Tourist songs

Many bards got known by singing туристической песни [turisticheskoy pesni] or tourist songs. They were written to praise the freedom which many young people experienced when they were camping outside the towns to go fishing, climbing mountains or sailing on the rivers. With this kind of activities, the youngsters tried to find values like courage, friendship, trust, cooperation and mutual support, which could not be found in the Soviet everyday life anymore.

In general, tourists songs were tolerated by the authorities. They were even officially categorized as самодеятельной песни [samedeyatelnoy pesni] or homemade songs. This term was part of an official policy called художественная самодеятельность [khudozhestvennaya samodeyatelnost] or amateur performing arts. It even became an often-subsidised leisure activity which was widely spread. Almost every company, cooperative or collective farms had a Palace of Culture, or at least a House of Culture which was intended for amateur art and leisure. In The Master and Margarita, Bulgakov parodied such activities in Chapter 17, when the employees of the branch of the Spectacles Commission in Vagankovsky Lane start singing Славное море, священный Байкал [Slavnoye morye, sviyashchenny Baykal] or Glorious sea, sacred Baikal.

At some universities there was a Клуб самодеятельной песни [Klub samodeyatelnoy pesni] or Club for homemade songs, basically a club for bard songs which stood apart from the mainstream Soviet policy of amateur performing arts.

Political songs

Even further away from the official policy were the bards who were known for their политические песни [politicheskiye pesni] or political songs. This genre could include right up front political songs, but also pure satire. Both Bulat Okudzhava and Vladimir Vysotsky made such songs, though the latter later evolved into the mainstream direction.

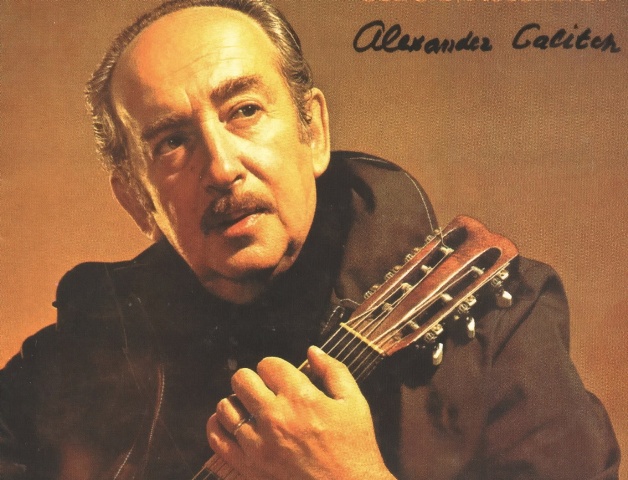

Another famous Russian bard, Aleksandr Arkadyevich Ginzburg (1918-1977), was forced to emigrate because of his political songs. His pseudonym was Aleksandr Galich. Citizens who had a cassette of his songs could be prosecuted. He was arrested by the KGB and in 1974 he emigrated. He went first to Norway and then to Germany, to end up in Paris.

Political songs which denounced capitalism and fascism, like the songs from the theatre plays of the German writer Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) were allowed to be sung, and were also often picked up by the bards.

Aleksandr Galich

Shansons

A third genre that was often practiced by bards was the блатная песня [blatnaya pesnja] or ribald song. In English, this genre is also known as the outlaw song, and in Russian the term Русский шансон [Russky shanson] or Russian chanson is often used. Chanson is the common French word for song.

The genre originated in the early twentieth century, before the Soviet Union even existed. The songs glorified life outside the law and broke with the structures and rules of the old Russian society. In the 30s, new songs emerged in the camps of the Gulag, which were about innocent people who were sent to labor camps. During the period of political thaw under Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev (1894-1974), a lot of these prisoners were released. They brought their songs with them, and bards as Aleksandr Moiseevich Gorodnitsky (°1933) picked them up and started to sing them. This gave a broader meaning to the term Russian chanson and it soon became a symbol of the struggle against oppression.

Aleksandr Moiseevich Gorodnitsky

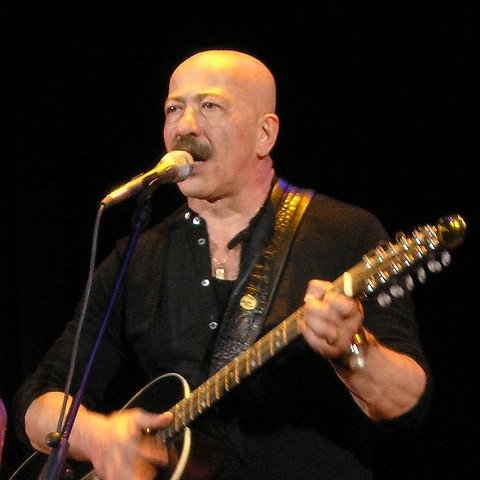

Aleksandr Rozenbaum

A well-known performer of ribald songs is Aleksandr Yakovlevich Rozenbaum (°1951). Inspired by the work of the Russian writer Isaak Emmanuilovich Babel (1894-1940), he wrote many humorous songs about the Jewish mafia in Odessa. In 1983, Rozenbaum wrote a song about The Master and Margarita. And in 2009 he sang the vocal part of doctor Stravinsky in the opera Master i Margarita, written by composer Alexander Borisovich Gradsky (°1949).

Aleksandr Yakovlevich Rozenbaum

Sergey and Tatyana Nikitin

Some bards did find their way into the formal system though. The song Aleksandra of the couple Sergey Nikitin (°1944) and Tatyana Nikitina (°1945), for example, became immensely popular by the movie Moscow Does Not Believe In Tears, with which director Vladimir Menshov (°1939) got the Oscar for Best Foreign film in 1981.

Tatyana and Sergey Nikitin

Click here to watch a video clip of Aleksandra by Sergey and Tatyana Nikitin

The bards and The Master and Margarita

Even today the tradition of the bards is still continued in Russia. As a matter of fact, many of the modern Russian bards have made songs about The Master and Margarita. You can read more about it in our section Music inspired by the novel.

Click here to read more about the influence of The Master and Margarita on the Russian bards