Artists and censorship

Narkompros, Glavlit, Glavrepertkom and others

Being a writer was not an easy job in the Soviet Union. Either you wrote according to the rules prescribed by the party - and covering the subjects determined by it - either you were confronted with censorship or worse, like arrest, deportation or execution.

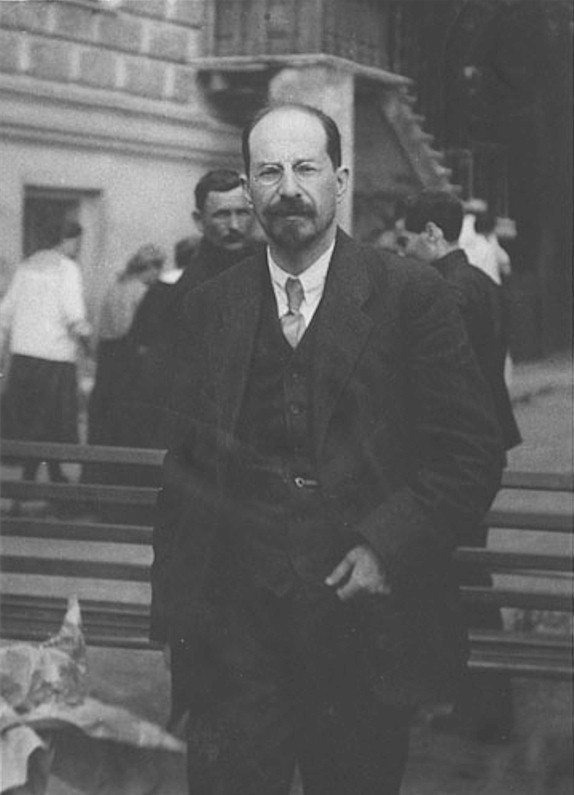

A first important institution which played a distinguished role in the censorship in the Soviet Union was the Народный комиссариат просвещения (Наркомпрос) [Narodny komissariat prosveshcheniya] (Narkompros) or the People's Commissariat for Enlightenment. The translation can be subject to discussion, since the word просвещение [prosveshchenie] also means educatoin, information and civilisation. Anyway, the Narkompros was the Soviet administration in charge of national education and other area's related to culture and sciences. From the October revolution to 1929, the critic and journalist Anatoly Vasilevich Lunacharsky (1875-1933) was heading the organisation. At first Lunacharsky protected avant-garde artists like Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1893-1930), Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (1879-1935) and Vladimir Yevgraphovich Tatlin (1885-1953). He helped his brother-in-law Alexander Aleksandrovich Bogdanov (1873-1928) to establish the пролетарская культура [proletarskaya kultura] or proletarian culture, abbreviated to пролеткульт [proletkult], which was a movement that would be the basis for «real proletarian art», averse from all «bourgeois influences». But it was also Lunacharsky who organized the first campaigns of censorship in the Soviet Union and who was heavily opposed to Bulgakov, which made him the prototype of the critic Latunsky in The Master and Margarita. When Stalin consolidated his power, Lunacharsky lost all of his important positions in the government and he was appointed ambassador to Spain.

Anatoly Vasilevich Lunacharsky

The Narkompros had a number of different sections. In addition to the main ones related to education in general, it also enclosed the Главное управление по делам литературы и издательств (Главлит) [Glavnoe upravlenie po delam literatury i izdatelstv] (Glavlit) or the Central Administration for Literature and Publishing affairs, a section created in 1922 and meant to prevent the publication of state secrets and thus responsible for censoring of what was published.

Another department of the Narkompros, the Главный репертуарный комитет (главрепертком) [Glavny repertuarny komitet] (Glavrepertkom) or Central Committee for Repertoires, was created in 1923 for approval of the theatre repertoires. Especially the Glavrepertkom caused Bulgakov much trouble. Time after time they banned his plays from the theatres where they were planned to be played.

In 1927, a new organisation was created, the Главное управление по делам художественной литературы и искусства (Главискусство) [Glavnoe upravlenie po delam khudozhestvennoy literatury i iskusstva] or Central Directorate for Literature and Art Affairs (Glaviskusstvo) to co-ordonate the activities of various administrations dispersed in various departments of the Narkompros.

In 1936 the organisation of the censorship authorities was completed with the Управления театральных зрелищных предприятий (УTЗП) [Upravleniya teatralnykh zrelishchykh predpiyaty] (UTZP) or Directorate for Theatre Enterprises which was meant to to provide a single agency authority over all troupes, estimated at approximately nine hundred. In Moscow there was also the Управления Московских зрелищных предприятий Наркомпроса (УМЗП) [Upravleniya Moskovskikh zrelishchykh predpiyaty Narkomposa] (UMZP) or Directorate for Moscow Entertainment Enterprises belonging to the People's Commissariat of Enlightenment.

The UTZP and the UMZP were, together with the Glavrepertkom, located on Чистые пруды [Chistye Prudy] or Clean Ponds, where Bulgakov situated the fictitious Acoustics Commission of the Moscow theatres of Arkady Appolonovich Sempleyarov.

The building on Chistye Prudy

In addition to the organisations of the Narkompros, the work of writers could be controlled or censored by the Объединение государственных книжно-журнальных издательств (ОГИЗ) [Obedinenie gosudarstvennikh knizhno-zhurnalnykh izdatelstv]] (OGIZ) or State Union of Book and Magazine Publishers, which operated under direct supervision of the Council of the People's Commissars, the Sovnarkom, and by theГосударственного объединения музыки, эстрады и цирка (ГОМЕЦ) [Gosudarstvennogo obedineniya muzyki, estrady i tsirka] (GOMEC) or the State Union for Music-Hall, Concert- and Circus Enterprises.

And, in closing, the secret service of the NKVD had, since 1920, a bureau to exercise control over literature, It was called Литконтроль [Litkontrol] and it had to «monitor the life, the creative work, the moods, the friendships, and the statements of all Soviet writers».

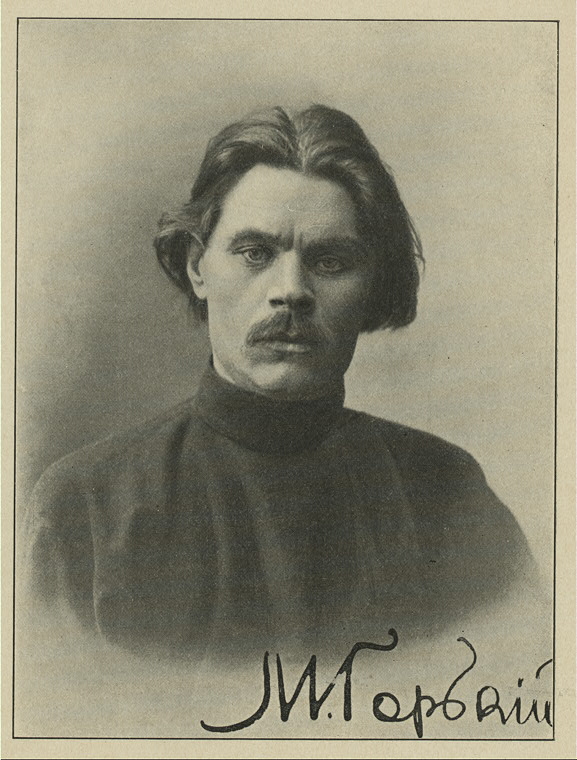

Social Realism and the Writers' Union

The ideology of the Communist Party wanted to influence the creative processes from the first moment of artistic inspiration. The party was supposed to be the artist's muse. Therefor Social Realism was introduced in 1932 as the only acceptable aesthetic form. The merits of a work of art were measured to its contribution to the advancement of socialism for the mass. In 1932 the Союз советских писателей [Soyuz sovietskikh pisateley] or the Soviet Writers' Union was created by a Party decree to make literators toe to the line of marxism-leninism. This Union replaced the existingРоссийская Ассоциация Пролетарских Писателей (РАПП) [Rossyskaya assotsiatsiya Proletarskikh Pisateley] (RAPP) or theRussian Association of Proletarian Writers. The first Congress of the Writers' Union, presided by Maxim Gorky (1868-1936), was organised in 1934. The Writers' Union was one of the many творческиесоюзы [tvortsheskye soyuzi] or artistic unions, so-called «voluntary» associations, comparable to labour unions, but completely under control of the Party. And even more: they controlled the activities of their members.

Maxim Gorky

Under the influence of Proletkult (see above), Russian artists were prominent players in international arts movements like constructivism and kubism. But the Social Realism would soon made an end to this role.

The Государственный комитет по делам издательств, полиграфии и книжной торговли СССР (Госкомиздат) [Godudarstvenny komitet po delam izdatelstv, poligrafy i knizhnoy torgovli SSSR] (Goskomizdat) or the State Committee for Publishers, Printers and Book Trade in the Soviet Union made, together with the secretariat of the Writers' Union, all decisions about publications. Even paper supply was a hidden form of the censor mechanism. This explains why, in the novel, when Pilate asks Matthew Levi to accept something from him, the latter answers: «Have them give me a piece of clean parchment».

The social command

The policy toward literature adopted by the Communist party in 1928 is characterized by the term Социальный заказ [sotsialniy zakaz] or the social command. It was in connection with the first Five-Year Plan and carried out by RAPP and the editorial boards of publishing houses. Under this policy, specific themes were dictated to writers with the goal of stimulating socialist construction and to further the ideological ends of the state. Statements of RAPP leaders make it clear that they supported such historical themes, if treated from the proper Marxist point of view. The theme assigned to Bezdomny in The Master and Margarita, while not directly connected with the Five-Year Plan, was atheism.

Bulgakov is specifically ridiculing this social command in the novel when his hero, the master, recalls that the editor to whom he submitted his manuscript asked him, what in his opinion was a totally idiotic question: «who had given him the idea to write a novel on such a strange theme?» It was obviously not in his social command to write a novel about Pontius Pilate.