Мы продолжаем напряженно работать, чтобы улучшить наш сайт и перевести его на другие языки. Русская версия этой страницы еще не совсем готова. Поэтому мы представляем здесь пока английскую версию. Мы благодарим вас за понимание.

Михаил Александрович Берлиоз

Context

Mikhaïl Alexandrovitch Berlioz is editor of «a fat literary journal», and chairman of the board of one of the major Moscow literary associations, called Massolit. He's a middle-aged man, a typical representative of the intellectual elite, a good follower of the official policy. So it is clear that he can't follow the dissentient opinions shown off by Woland when they met at Patriarch's Ponds. And certainly not his supernatural gifts. Because this strange foreigner know their names and surnames, and he know that he's having an uncle in Kiev. And he knows much more...

- «Did you come alone or with your wife?»

- «Alone, alone, I'm always alone,» the professor replied bitterly.

- «And where are your things, Professor?» Berlioz asked insinuatingly.

- «At the Metropol? Where are you staying?»

- «I? ... Nowhere,» the half-witted German answered, his green eye wandering in wild anguish over the Patriarch's Ponds.

- «How's that? But... where are you going to live?»

- «In your apartment,» the madman suddenly said brashly, and winked.

- «I... I'm very glad ...» Berlioz began muttering, «but, really, you won't be comfortable at my place ... and they have wonderful rooms at the Metropol, it's a first-class hotel...»

During this dialogue Berlioz couldn't obviously know yet that he would never return to his apartment at Bolshaya Sadovaya 302-bis, and that Woland would soon move in there.

Berlioz is the prototype of the faithful adherent who makes his career by his devotion to the policy, rather than by his own intellectual capacities. As long as he sees Woland as a strange historian, an ignorant tourist, he declaims the official policy that Jesus never existed. But when he understands that the professor out-classes him intellectually, he gets more cautious. But he doesn't accept the logics of the different opinion, and he no longer argues with it. On the contrary, the more the opinions of the strange visitor differ from what is officially proclaimed, the more he's convinced that he's confronted with a madman. Someone from whom you should take distance and, above all: someone who should be reported.

At that moment, Berlioz acts like a sly tell-tale who keeps his mouth shut, waiting for the right moment. Woland asks him whether there's no devil either. When Berlioz notices that young Ivan is ready to reply «no» to this question, he whispers: «Don't contradict him», and he did this, as Bulgakov described it, «with his lips only, dropping behind the professor's back and making faces». But, alas, when he runs to the nearest public telephone to inform the foreigners' bureau, thus and so, that «there's some consultant from abroad sitting at the Patriarch's Ponds in an obviously abnormal state» he is decapitated by a tram.

Massolit

Massolit is an invented but plausible contraction parodying the many contractions introduced in post-revolutionary Russia. There will be others further on in the novel - like the Dramlit House (House for Dramatists and Literary Workers) and findirector (financial director).

In Bulgakov’s time, the writers needed to be members of official literary unions if they wanted their works to be published. Some examples of such unions were the Российская Ассоциация Пролетарских Писателей (РАПП) [Rossiyskaya Assotsiatsiya Proletarskikh Pisateley (RAPP)] or the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers and the Московская Ассоциация Пролетарских Писателей (MAPP) [Moskovskaya Assotsiatsiya Proletarskikh Pisateley (MAPP)] or the Moscow Association of Proletarian Writers. The names of these organisations are real: many hideous abbreviations were commonly used in the Soviet Union.

Bulgakov based the fictional Massolit on the RAPP and the MAPP. In the book he gives no explanation to the abbrevation. But it probably was the Мастера Социалистической литературы [Mastera Sotsialisticheskoy literatyry] or Masters for Socialist Literature, by analogy with the Мастера Коммунистической Драмы (Масткомдрам) [Mastera Kommunisticheskoy Dramy (Mastkomdram)] or Masters for Communist Drama, an organisation that really existed in Bulgakov's era. Mastkomdram was created on November 29, 1920 as an initiative of the TEO, the Theatre Division of the Commissariat of Education and Enlightenment, and lead by theatre director and actor Vsevolod Emilevich Meyerhold (1874-1940).

Всеволод Эмильевич Мейерхольд

Berlioz

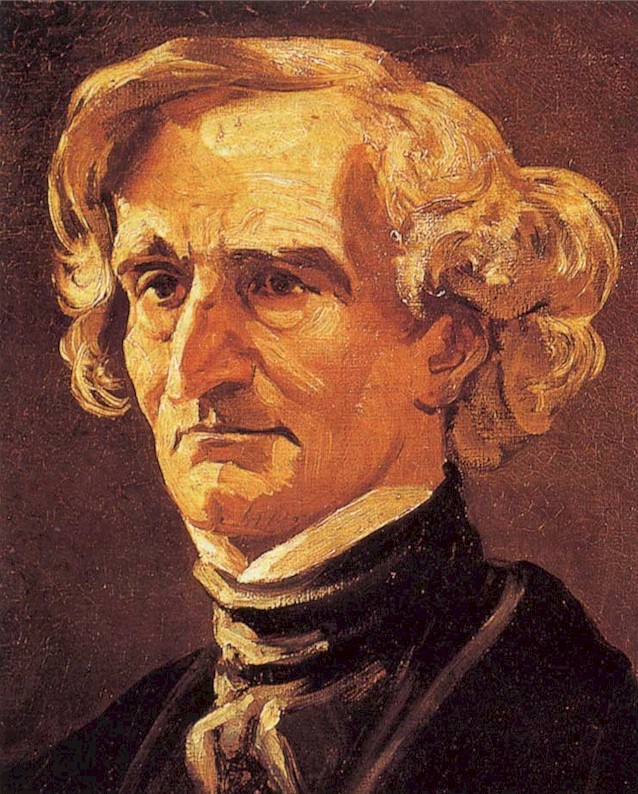

Just like the Rimsky and Stravinsky characters, Mikhail Aleksandrovich shares his name with a composer, Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), who wrote La Damnation de Faust (The Damnation of Faust, 1846), a concert opera based on Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1842). In Berlioz' opera there are four characters: Faust (tenor), de devil Méphistophélès (bariton), Marguerite (mezzosopraan) and Brander (bas).

Hector Berlioz wrote also the well-known Symphonie Fantastique (1830), one of the most famous examples of programme music. In the fourth movement of this symphony - Marche au supplice (March to the scaffold) - the main character is seeing his own decapitation in his dream, and in the fifth movement - Songe d'une nuit du sabbat (Dream of a witches' sabbath) - he sees himself at a witches' sabbath in a giant orgy.

For the lovers of trivia: composer Hector Berlioz studied, like Bulgakov, medicine before he focussed totally on art. And the character of Mikhaïl Alexandrovitch Berlioz has got the samen initials as Mikhail Afanasievich Bulgakov.

Гектор Берлиоз

The decapitation of Berlioz

The decapitation of Berlioz could have been inspired by a story that was told in relation with Nikolay Vasilievich Gogol (1809-1852), author of Dead Souls. It was told that the Soviets, when they wanted to exhume the body of Nikolai Gogol at the Danilov Monastery in Moscow in 1931 to bury him elsewhere, found his body without its head. There were stubborn rumours that Aleksey Aleksandrovich Bakhrushin (1865–1929) had stolen the skull. Bakhrushin, a successful business man and member of the Moscow city council, honorary member of the Royal Academy for Sciences and one of the founding fathers of the Russian Theatre Association, was collector of theatre memorabilia, and he would have ordered to steal Gogol's skull in 1909.

Николай Васильевич Гоголь

It has never been proved whether this story was true. But it is a fact that Bakhrushin had an impressive theatre collection. It is still permanently exhibited in the famous A. A. Bakhrushin National Central Theatre Museum in Bakhrushin ulitsa 31, in the Zamoskvoreshe district, one of the most picturesque neighbourhoods in Moscow.

Алексей Александрович Бахрушин

Other interpretations

According to Georgy Aleksandrovich Lesskis (1917-2000), who wrote the comments to a Moscow edition of the novel in 1990, Berlioz' character is based on the People's Commissar for Education, Enlightenment and Sciences Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (1875-1933). Another Bulgakov expert however, the self-willed Ukrainean polemicist Alfred Nikolayevich Barkov (1941-2004), is convinced that Lunacharsky was the prototype for the critic Latunsky.

According to the Russian Bulgakov expert Boris Vadimovich Sokolov (°1957), the author of the Bulgakov Encyclopedia, the name Массолит [Massolit] would be an abbreviation of Масонские литературы [Masonskie literaturi] or Masonic writers. Sokolov argues his thesis by referring to an article written by Afanasy Ivanovich Bulgakov (1859-1907), theologian and church historian, and father of Mikhail Afanasievich. In 1903, he had written an article about Modern Freemasonry in its Relationship with the Church and the State, which was published in the Acts of the Theological Academy of Kiev. Bulgakov Senior wrote that the Masons wanted to introduce a new faith. A false faith, according to him, because their only aspiration would have been to increase the personal wealth of the members. However, it seems somewhat farfetched to link the name Massolit to Freemasonry. In that case, Bulgakov would have written Масолит [Masolit], with only one «s», which not.

Bulgakov was interested in the symbols of Freemasonry, however, and he refers to them indeed on various places in the novel.

Борис Вадимович Соколов