12. Black Magic and its Exposure

English > The novel > Annotations per chapter > Chapter 12

The title

In 1928, in the period that Bulgakov began to write the first version of The Master and Margarita, Harry August Jansen (1883-1955) was on tour in Moscow. He was an American artist of Danish origin, who performed as Dante the Magician. Through his make-up he looked like Mephistopheles, the devil that appears in the Faust of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). One of the places where he performed was the Music Hall in Moscow, which was the prototype of the Variety Theatre. According to the audience, he looked at them «with the condescending smile of a devil-philosopher».

In 1940, Harry Jansen published Sim-Sala-Bim, 50 Tricks For Everybody, a programme brochure of 28 pages, in which he «exposed» several of his tricks himself.

In the Russian title of chapter 12 the word разоблачение [razoblatsyenye] is used for «exposure». It is composed by the preposition раз- [raz-], which means out-, and the verb облачить [oblachit], which means something like dress up. We will see that dressing up - and getting undressed again - will play an important role in this chapter.

The Giulli family

In the 30’s, the Труппа Польди [Truppa Poldi] or the Poldi company - artist name for the Podrezov family - showed its bicycle tricks in the Moscow Music Hall. On posters from that time the man in the yellow bowler-hat and the blond woman on a single wheel can be recognized. Bulgakov writes that the woman is wearing a трико [triko], the Russian transliteration of tricot or jersey - the first of many French words he will use in this chapter.

Where he had gone...

Of course, Rimsky knew very well where Varenukha had gone - he had sent Varenukha to the secret service NKVD himself to «let them sort it out» - but he doesn't even dare to think the name of the secret police to himself.

But what for?

Varenukha did not come back from the not mentioned place. That almost obviously made Rimsky suppose that he was arrested. But he hesitates to call, because the unmentioned secret police is not an authority which you spontaneously contact on your own initiative. Because, one day, it could be turned against you.

This certainly unpleasant, though hardly supernatural occurrence

Again Bulgakov's humor here is at the expense of the Soviet reality. Telephones, even to this day, are extremely unreliable in Russia.

A messenger came in

In the original text, Bulgakov is using again the Russian transliteration of a French word, he writes курьер [kuryer], a transliteration of the French word courrier or messenger boy. The announcement of the messenger makes Rimsky wince with pain. Not only must he allow the performance of a black magic show that he didn’t approve of in the first place, he also knows that he is the only one left to greet the foreign artiste. He turns «blacker than a storm cloud» - a foreshadowing of the upcoming scene in which money rains down from the ceiling - and heads backstage to welcome the foreigner.

Bengalsky

The Bengalsky character is a symbol for the «political educators» who took an active part in Soviet society - Mikhail Bulgakov hated them. So he is promptly decapitated. The Bengalsky character is based on Vladimir Ivanovich Nyemirovich-Danchenko (1858-1943), one of the directors of the Moscow Art Theatre MKhAT. Bulgakov called him an «old cynic». He was longing to show his novel to this «philistine». In his Theatrical novel Bulgakov presented this Vladimir Ivanovich on the bank of the river Ganges. Maybe that's an explanation for the name Bengalsky.

Bengalsky's decapitation was probably inspired by a scene from the novel Metamorphoses, also known as The Golden Ass, written by the romanized Berber Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis (123 BC- 80 BC). Metamophfoses is the only Latin novel which was preserved in its entirety. In this novel, the witch Moreya tears off the head of the main character, Socrates, and puts it back intactly.

Click here to read a comprehensive description of Bengalsky

An armchair

Woland's position in the theater is in a seat while he is watching the audience, which is a reversal of what we could expect. And indeed, the Muscovites in the audience end up putting on more of a show than Woland himself.

The checkered clown

Bulgakov described a клетчатого гаера [kletchatogo gayera] or a checkered gaillard, which is again a Russian transliteration of a French word. Originally, the word gaillard refers to a renaissance dance and the associated music, but it is also used for «a guy», «a fellow» or «a strapper»: a (young) man full of vigor, strength and health.

What do you think, the Moscow populace has changed significantly, hasn't it?

While this statement would not normally be considered offensive, in the Soviet Union under Stalin it was a very subversive question to ask. According to the Communist Party line, the people of the Soviet Union had arrived into the utopia of Communism. They were new Soviet men and women. The Homo soveticus was a quite different species from any other human being on earth. They worked harder, knew more and were happier than anyone else. For Bulgakov to claim otherwise was dangerous.

Trams, automobiles...

While it appears that Woland is answering the question seriously and thoughtfully, Bulgakov does little to veil his sarcasm. In the author’s diary entry of August 9, 1924, he writes that they have introduced buses in Moscow, but that there are very few of them. On December 20-21, 1924 he writes: «They’re working out a new traffic scheme… But there is no traffic, because there are no trams. And it’s laughable, but there are only eight buses for the whole of Moscow».

Knowing how much Bulgakov cursed the public transportation system, one can only imagine the sarcasm he intended in these lines. Woland seems to be saying that while the city appears to have changed outwardly (and no doubt, the authorities praise these fine improvements in public transportation), there really are no significant changes for the better. Meanwhile, Grigory Rimsky grows pale and tense, fearing what Woland might say next.

If it weren't for poker

Poker, like other card games, was looked upon with sorrow by the Soviets. This changed dramatically after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Moscow, and other cities as well, is swarmed with casino’s. At the end of 2006 some of them were closed because they were connected to the Georgian maffia.

Behemoth

In the biblical Book Job 40:10-19 is a description of a huge monster, in Hebrew called Behemoth. Bible translators didn't know which way to go with this word for a long time because they didn't know any beast with «a tail like a cedar and an enormous power in his abdominal muscles and loins». Some chose for an elephant, others for a hippopotamus but they all knew that neither of these could be accurate. That's why English translators leave the word Behemoth as it is. Бегемот [Begemot] is also Russian for hippopotamus. In Chapter 17, the pretty Anna Richardovna, the secretary of Prosha Prochor Petrovich, describes Behemoth as «a tomcat, black, big as a hippopotamus».

In circles of devil experts, Behemoth is the devil of the desires of the stomach. It could explain why he's so interested in the food at the currency store Torgsin in Chapter 28.

According to Bulgakov's second wife Lyubov Evgenevna Belozerskaya (1895-1987) the prototype for Behemoth was their own pet Flyushka, a big grey cat.

Click here for a comprehensive description of Behemoth

By God, they're real! Ten-rouble bills!

The English translators of The Master and Margarita - just like their Dutch and French colleagues - obviously missed some of Bulgakov's satire here. Because they translated as follows:

- «By God, they're real! Ten-rouble bills!» joyful cries came from the gallery.

In the original Russian text though, Bulgakov did not write about roubles, he described another monetary unit from the Soviet period, the chervonets. A correct translation would have been:

- «By God, they're real! Chervontsi!» joyful cries came from the gallery.

Bulgakov never uses the term ten-rouble bills in The Master and Margarita. He always writes червонец [chervonets] or its plural червонцы [chervontsy], which gives a complete other dimension to the question if the bills «were real or some sort of magic ones». The chernovets was indeed the new official monetary unit introduced by the Soviet government in 1922 to stop the hyperinflation and restrain chaos in the money standard during the civil war. It became and remained the official currency in the Soviet Union until 1947.

However, the Soviet regime did not dare to abolish the rouble. For 25 years, the country has known two currencies: the official chervonets - distrusted by everyone - and the «good old rouble». There was, however, no exchange rate between the two currencies, and officially only the chervonets could be used.

In The Master and Margarita Bulgakov criticizes the use of the chervonets more than once. In Chapter 18, the chervontsi which fell from under the cupola into the theatre change into cut-up paper, in labels of Narzan mineral water, in labels of Abrau-Durso wine, or in foreign currency. Such strange things happen only to chervontsi, never to roubles. Still in chapter 18, the taxi-drivers at the Variety Theatre only wants to take Vasily Stepanovich Lastochkin if he pays with Трешки [treshki] or three-roubles bills. He accepts only «good, solid roubles», not chervontsi. For the Soviet citizens did not trust this currency imposed by the authorities.

It's a pity that most translators of The Master and Margarita always translate the word червонец [chernovets] by ten-rouble bill because, by doing so, they miss an essential part of Bulgakov’s satire on the subject of money in the Soviet Union.

Click here to read more about the chervontsi

Here you can read when and why Bulgakov uses the word 'chervonets"

Avec playzeer

Again, Bulgakov is using Cyrillic transliterations of French words. In the Russian text, we can read Авек плезир [Avek plezir], the Cyrillic transliteration of the French Avec plaisir, which means with pleasure. A little further in the text, Bulgakov uses the word бельэтаж [beletazh], the transliteration of the French bel étage, to refer to the theatre's mezzanine, but the English reader won't know this, since Pevear and Volokhonsky translated it as the dress circle.

Capricious notes

Here's another transliteration of a French word: in the Russian text, Bulgakov writes капризные бумажки [kapriznye bumazhki] or capricious pieces of paper.

Why would Bulgakov pepper the show of Woland and his retinue with so many foreign words, particularly from the French? And how is Woland, the «visiting professor from Germany,» able to address the Muscovites in their native tongue with no perceivable accent (except when he chooses to speak with one)? The answer is clear. Woland, after all, is the devil, so he is able to speak in any language and appeal to any group of people in their native tongue. John 8:44 reads: «You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father's desire… When he lies, he speaks his native language, for he is a liar and the father of lies».

Woland uses French exclamations and forms of address with the spectators at the Variety Theater, because French is seductive and is the language of high society. He employs this pretentious use of the language to appeal to the vanity of Muscovites and to their desire to be held in that light.

Marred by a queer scar on her neck

Gretchen - the Margarita from Goethe’s Faust - had exactly the same mark as Hella in the scene on Walpurgis Night.

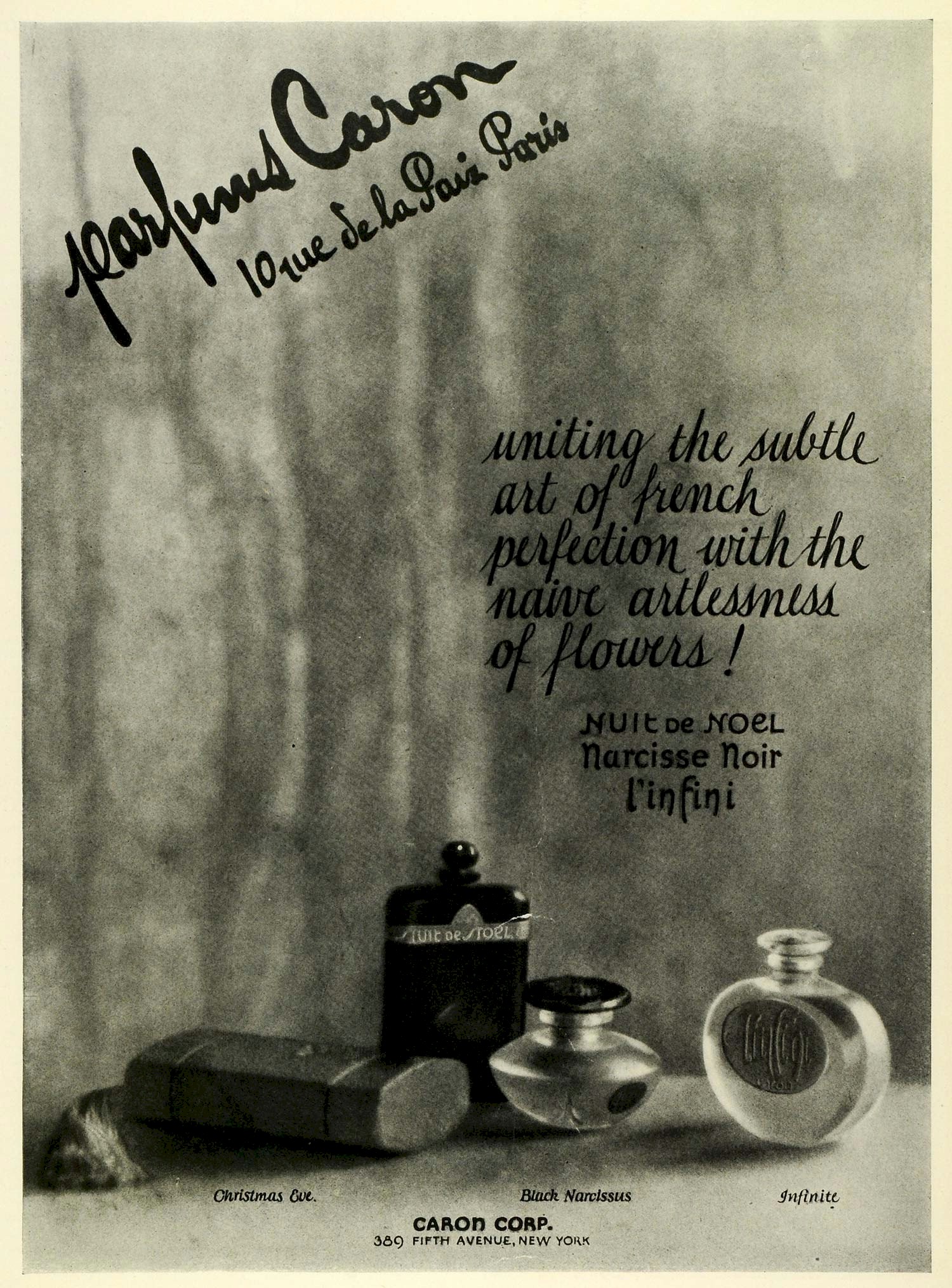

Guerlain, Chanel No. 5, Mitsouko, Narcisse Noir

Obviously, Parisian clothing and perfumes would have been completely inaccessible to the average Soviet woman. The incomprehensible but seductive words of the perfume brands are all phonetically written in Russian letters. In the Russian text Bulgakov writes about Герлэн, шанель номер пять, мицуко, нарсис нуар which are, again, the Russian transliterations of the famous French brands Guerlain, Chanel No. 5, Mitsouko and Narcisse Noir.

Bulgakov chooses the perfumes deliberately, not simply naming well-known fragrances but rather selecting ones that have a connection to Russia. The first one mentioned, Guerlain, is a famous French perfume house named after Pierre-François Pascal Guerlain (1798-1864), the preferred perfumer of all the courts in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. The founder of the company earned the prestigious French title of Parfumeur breveté de sa Majesté, which led him to create perfumes for, among others, Queen Victoria (1819-1901) of England, Queen Isabella (1830-1904) of Spain, and Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (1878-1918) of Russia, the youngest son of Alexander III (1845-1894).

Mitsouko, created in 1919 by Jacques Guerlain (1874-1963), the grandson of the founder of the perfume house Guerlain, is said to have been inspired by the name of the heroine of the novel La Bataille (The Battle), written by Claude Farrère (1876-1957) in 1909. It is the story of an impossible love between Mitsouko, the wife of the Japanese Admiral Togo, and a British officer. The story takes place in 1905, during the war between Russia and Japan. Both men go to war, and Mitsouko, hiding her feelings with dignity, waits for the outcome of the battle to discover which of the two men will come back to her and be her companion for life.

The perfume Chanel No. 5 was created by Ernest Beaux (1881-1961), a Russian and French perfumer born in Moscow. According to his colleagues, the No. 5 fragrance was a remake of one of the perfumer’s earlier creations called Букет де Екатерины [Bouquet de Cathérine]. It had been created as an homage to Catherine the Great (1729-1796) and released in 1913 to celebrate the three-hundredth anniversary of the rise of the Romanov dynasty. It was produced by Rallet & Company, the largest Russian perfume house and purveyor to the courts of Imperial Russia.

Finally, Narcisse Noir was created by Ernest Daltroff (1867-1941), the founder of the famous French perfume house Caron, in 1911. Daltroff was a chemist and perfumer from Russia who had been born into a wealthy bourgeois family of Russian Jews and later emigrated to France. Bulgakov's reference to this particular fragrance is wonderfully appropriate given its name, Black Narcissus. The colour black has an aura of the occult and the forbidden, both of which are important elements in this scene. Narcissus was the youth from Greek mythology who fell in love with his own image reflected in a pool and wasted away from unsatisfied desire, whereupon he was transformed into the flower. In this scene, the ladies in the audience are transformed through Parisian attire from humble Soviet citizens into pretentious, vain narcissists, as the next scene demonstrates.

Click here to read more about foreign words in Russian

Arkady

The so called Acoustics Commission of the Moscow theatres did not exist in reality. Bulgakov based this institution very probably on the Управления театральных зрелищных предприятий (УTЗП) [Upravleniya teatralnykh zrelishchykh predpiyaty] (UTZP) or the Directorate for Theatre Enterprises belonging to the Народный комиссариат просвещения (Наркомпрос) [Narodny komissariat prosveshcheniya] (Narkompros) or the People's Commissariat of Enlightenment. The Narkompros had a number of different sections to control education and arts in the Soviet Union.The UTZP, created in 1936, was meant to to provide a single agency authority over all theatre troups, estimated at approximately 900.

Bulgakov situates his Commission on Чистые пруды [Chistye Prudy] or Clean Ponds. In the Soviet era there were, indeed, three organisations responsible for guarding - and especially censoring - a variety of arts in a building on Chistoprudny Boulevard no. 6. One of them was the UTZP. Another organisation located in this building was the Главный репертуарный комитет (Главрепертком) [Glavny repertuarny komitet] (Glavrepertkom) or the Central Committee for Repertoires, created in 1923, which had to approve theatre playes before they could be staged.

Arkady Sempleyarov lived, according to Bulgakov, at the Каменный мост [Kamenny Most] or Stone Bridge in the Дом на набережной [Dom na neberezhnoy] or the House on the Embankment. In reality, a man called Yakov Stanislavovich Ganetsky (1879-1937) lived at this address. He was the director of the Государственного объединения музыки, эстрады и цирка (ГОМЕЦ) [Gosudarstvennogo obedineniya muzyki, estrady i tsirka] (GOMEC) or the State Union for Music-Hall, Concert- and Circus Enterprises, one of the organisations which could censor authors and playwrights.

The UTZP was under command of Mikhail Pavlovich Arkadyev (1896-1937) - probably the source of inspiration for Arkady Sempleyarov's first name. You can read more about the UTZP in the Context section of the Master & Margarita website.

According to the Bulgakov Encyclopaedia, the surname Sempleyarov would come from the name of a good friend of Bulgakov’s, composer and director Alexander Afanasevich Spendiarov (1871-1928). But Spendarov was not as self-satisfied and arrogant as the Sempleyarov of the Variety Theatre. On the contrary, he was rather anxious and absent-minded, like the Sempleyarov we meet later in the novel, in Chapter 27, when he is summoned to come to the office of the secret police.

For the more assertive, big-headed Sempleyarov in the theatre, Bulgakov was rather inspired by the character of Avel Sofronovich Enukidze (1877-1937), a Georgian who, from 1922 to 1935, was chairman of the boards of the Bolshoy Theatre and the Moscow Art Theatre MKhAT. Enukidze was also member of the Narkompros, the Soviet People's Commisariat for Education, of which some departments had their offices at Chistoprudny Boulevard no. 6, where Bulgakov situated the Acoustics Commission of the Moscow theatres. Enukidze was much attracted by the female beauty, and he was particularly interested in the actresses of the theatres submitted to his Commission. In June 1935 he was removed from his party functions, and in December 1937 he was sentenced and executed for terrorist acts against the native country and espionage. Together with him was sentenced and executed baron Boris Sergeevich Steiger (1892-1937), the prototype of baron Meigel in the novel.

Both Sempleyarov's intervention in the Variety Theatre and the situation with the niece from Saratov remind to Vsevolod Emilevich Meyerhold (1874-1940), an enthousiast activist of the Soviet theatre, but opponent to the Social Realism, who had worked in the Theatre department of the Narkompros until 1922, when he started his own Meyerhold Theatre in Moscow. In March 1936 he would have said in a discussion that «the masses of spectators ask for an explanation».

The link with the niece is made because Meyherhold had a close relationship with the Saratov region, and because his second wife, Zynaida Nikolaevna Reich (1894-1939) was twenty years younger than him. In 1939, when she was found dead in their apartment, Meyerhold was heavily tortured to make him confess that he had murdered her. He was sentenced to death and executed, probably on February 1, 1940.

The mass of spectators demands an explanation

«The mass of spectators» is typical Soviet jargon. Semplejarov asks his own question but he presents it like if it were the mass asking for it. «The people» or «the masses» were ostensibly in control.

The role of Louisa

Arkady’s young relation refers to the character Louisa Miller from the play Kabale und Liebe (Intrigue and Love), written by the German dramatist and writer Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805). The play, first performed in 1784 in Frankfurt, was a fixture in the repertories of Soviet theatres.

The rollicking words to this march

These words are Bulgakov’s free adaptation of a tune from a vaudeville from 1839, written by Dmitry Timofeevich Lensky (1805-1860). The title of the piece was Лев Гурыч Синичкин, или Провинциальная дебютантка or Lev Gurych Sinichkin, or a Provincial Debutante. It's the story of an old actor who desperately wants to offer a major role in the theatre to his talented daughter. But the powerful prima donna of the theatre company, a woman with a bad character and a whole network of relations, is standing in her way. After many heroic efforts and cheerful misunderstandings the old man's dream eventually comes true, and the star actress causes scandal with her patron. This vaudeville was performed from 1924 to 1931 in Moscow at the Vakhtangov theatre on the Arbat, alongside the apartment that Bulgakov had described in his theatre play Zoyka's apartment.

Director Alexander Arkadevich Belinsky (1928-2014) made a TV-movie of this vaudeville in 1974 - Лев Гурыч Синичкин (Lev Gurych Sinichkin). The leading roles were played by Nikolai Nikolaevich Trofimov (1920-2005) and Galina Georgievna Fedotova (°1949).

The song His Excellency which Bulgakov describes in The Master and Margarita doesn't sound exactly as in the original vaudeville. The so-called rollicking words of the march are as follows - at the top you can read Dmitri Lensky's original words, and below Bulgakov’s adaptation:

| Original (Russian) |

Original (translation Kevin Moss) |

| Его превосходительство Зовет ее своей И даже покровительство Оказывает ей. |

His Excellency calls her his own and even patronage renders to her. |

| Bulgakov's version (Russian) |

Bulgakov's version (Translation Pevear/ Volokhonsky) |

| Его превосходительство Любил домашних птиц И брал под покровительство Хорошеньких девиц!!! |

His Excellency reached the stage Of liking barnyard fowl. He took under his patronage Three young girls and an owl!!! |

Click here to hear the song in the TV-movie of Alexander Belinsky

Click here to see what Bulgakov made of it

Share this page |

Chapters

- Introduction

- 1 Never Talk with Strangers

- 2 Pontius Pilate

- 3 The Seventh Proof

- 4 The Chase

- 5 There were Doings at Griboedov's

- 6 Schizophrenia, as was Said

- 7 A Naughty Apartment

- 8 The Combat between the Professor...

- 9 Koroviev's Stunts

- 10 News From Yalta

- 11 Ivan Splits in Two

- 12 Black Magic and Its Exposure

- 13 The Hero Enters

- 14 Glory to the Cock!

- 15 Nikanor Ivanovich's Dream

- 16 The Execution

- 17 An Unquiet Day

- 18 Hapless Visitors

- 19 Margarita

- 20 Azazello's Cream

- 21 Flight

- 22 By Candlelight

- 23 The Great Ball at Satan's

- 24 The Extraction of the Master

- 25 How the Procurator Tried...

- 26 The Burial

- 27 The End of Apartment No. 50

- 28 The Last Adventures of Koroviev...

- 29 The Fate of the Master and...

- 30 It's Time! It's Time!

- 31 On Sparrow Hills

- 32 Forgiveness and Eternal Refuge

- Epilogue

English subtitles

All films based on The Master and Margarita are subtitled in English, French, German, Dutch, Spanish and Italian.

Illustrations

Poster for Dante in Moscow in 1928

The Poldi family

Vladimir Ivanovich Nyemirovich-Danchenko

Metamorphoses by

Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis

A chervonets or ten-rouble bill

Jacques Guerlain

The perfume Cuir de Russie by Chanel

Ernest Beaux

The perfume Narcisse Noir by Caron

The building of Glavrepertkom

at Chistye Prudy

The House on the Embankment

Yakov Stanislavovich Ganetsky

Alexander Afanasevich Spendiarov

Avel Sofronovitch Enukidze

Vsevolod Emilevich Meyerhold

Zynaida Nikolaevna Reich

Dmitry Timofeevich Lensky

The film Lev Gurytsj Sinichkin of

Alexander Belinsky